Case report with Dr. José Ignacio Zorzin

Rationalizing clinical workflows: This is the main reason for the use of universal products in adhesive dentistry. They are suitable for a wide range of indications and different application techniques, fulfil their tasks with fewer components than conventional systems and often involve fewer steps in the clinical procedure. Universal adhesives are a prominent example.

How do universal adhesives contribute to a streamlining of workflows?

When restoring teeth with resin composite, the restorative material will undergo volumetric shrinkage upon curing. By bonding the restorative to the tooth structure with an adhesive, the negative consequences of this shrinkage – marginal gap formation, marginal leakage and staining, hypersensitivity issues and the development of secondary caries – are prevented. The first bonding systems available on the dental market were etch-and-rinse adhesives, which typically consisted of three components: an acid etchant, a primer and a separate adhesive. Later generations combined the primer and the adhesive in one bottle, or were two or one-bottle self-etch adhesives. Universal adhesives (also referred to as multi-mode adhesives) may be used with or without a separate phosphoric acid etchant.

Fig. 1. Volumetric shrinkage of resin composite restoratives and its clinical consequences.

Which technique to choose depends on the indication and the clinical situation. In most cases, the best outcomes are obtained after selective etching of the enamel1. Bonding to enamel is generally found more effective when the enamel is etched with phosphoric acid, while the application of phosphoric acid on large areas of dentin involves the risk of etching deeper than the adhesive is able to hybridize. When the cavity is small, however, selective application of the phosphoric acid etchant to the enamel surface may not be possible, so that a total-etch approach is most appropriate. Finally, in the context of repair, the self-etch approach may be the first choice, as phosphoric acid might impair the bond strength of certain restorative materials by blocking the binding sites. By using a universal adhesive, all these cases may be treated appropriately, as the best suitable etching technique can be selected in every situation.

Apart from the differences related to the use or non-use of phosphoric acid etchant on the enamel or enamel-and-dentin bonding surface, the clinical procedure is always similar with the same universal adhesive. The following clinical case is used to illustrate how to proceed with CLEARFIL™ Universal Bond Quick (Kuraray Noritake Dental Inc.) in the selective enamel etch mode, and it includes some details about the underlying mechanism of adhesion.

How to proceed with selective enamel etching?

A clinical example.

This patient presented with a fractured maxillary lateral incisor, luckily bringing the fragment with him. Hence, it was decided to adhesively lute the fragment to the tooth with an aesthetic flowable resin composite.

Fig. 2. Patient with a fractured maxillary lateral incisor.

Fig. 3. Close-up of the fractured tooth.

Fig. 4. Working field isolated with rubber dam.

As proper isolation of the working field makes the dental practitioner’s life easier, a rubber dam was placed using the split-dam technique. It works well in the anterior region of the maxilla, as the risk of contamination with saliva from the palate is minimal. Once the rubber dam was placed, the bonding surfaces needed to be slightly roughened to refresh the dentin. As the surfaces were also slightly contaminated with blood and it is important to have a completely clean surface for bonding, KATANA™ Cleaner was subsequently applied to the tooth structure, rubbed into the surfaces for ten seconds and then rinsed off. The cleaning agent contains MDP salt with surface-active characteristics that remove all the organic substances from the substrate. The fragment was fixed on a ball-shaped plugger with (polymerised) composite and also cleaned with KATANA™ Cleaner.

Fig. 5. Cleaning of the tooth …

Fig. 6. … and the fragment with KATANA™ Cleaner.

What followed was selective etching of the enamel on the tooth and the fragment for 15 seconds. Whenever selective enamel etching is the aim, it is essential to select an etchant with a stable (non runny) consistency – a property that is offered by K-ETCHANT Syringe (Kuraray Noritake Dental Inc.). Both surfaces were thoroughly rinsed and lightly dried before applying CLEARFIL™ Universal Bond Quick with a rubbing motion. This adhesive is really quick: Study results show that the bond established immediately after application is as strong and durable as after extensive rubbing into the tooth structure for 20 seconds.2,3 The adhesive layer was carefully air-dried to a very thin layer and finally polymerized on the tooth and on the fragment.

Fig. 7. Selective etching of the enamel of the tooth …

Fig. 8. … and the fragment with phosphoric acid etchant.

Fig. 9. Application …

Fig. 10. … of the universal bonding agent.

Fig. 11. Polymerization of the ultra-thin adhesive layer on the tooth …

Fig. 12. … and the fragment.

What happens to dentin in the selective enamel etch (or self-etch) mode?

After surface preparation or roughening, there is a smear layer on the dentin surface that occludes the dentinal tubules, forms smear plugs that protect the pulp and prevents liquor from affecting the bond. When self-etching the dentin with a universal adhesive, this smear layer is infiltrated and partially dissolved by the mild self-etch formulation (pH > 2) of the universal adhesive. At the same time, the adhesive infiltrates and demineralizes the peritubular dentin. The acid attacks the hydroxyapatite at the collagen fibrils, dissolves calcium and phosphate and hence enlarges the surface. Then, the 10-MDP contained in the formulation reacts with the positively loaded calcium (and phosphate) ions. This ionic interaction is responsible for linking the dentin with the methacrylate and thus for the formation of the hybrid layer.4,5

In the total-etch mode, the phosphoric acid is responsible for dissolving the smear layer and demineralising the hydroxyapatite. This leads to a collapsing of the collagen fibrils, which need to be rehydrated by the universal adhesive that is applied in the next step. Whenever the acid penetrates deeper into the structures than the adhesive, the collagen fibrils will remain collapsed. This will most likely result in clinical issues including post-operative sensitivity6.

When applying the adhesive system, a dental practitioner rarely thinks about what is happening at the interface7. However, every user of a universal adhesive should be aware of the fact that a lot is happening there. This is why it is so important to use a high-performance material with well-balanced properties and strictly adhere to the recommended protocols.

Fig. 13. Schematic representation of dentin after tooth preparation: The smear layer on top with its smear plugs occluding the dentinal tubules protects the pulp and prevents liquor from being released into the cavity.

Fig. 14. Schematic representation of dentin after the application of a universal adhesive containing 10-MDP: The mild self-etch formulation partially dissolves and infiltrates the smear layer, while at the same time demineralizing and infiltrating the peritubular dentin5.

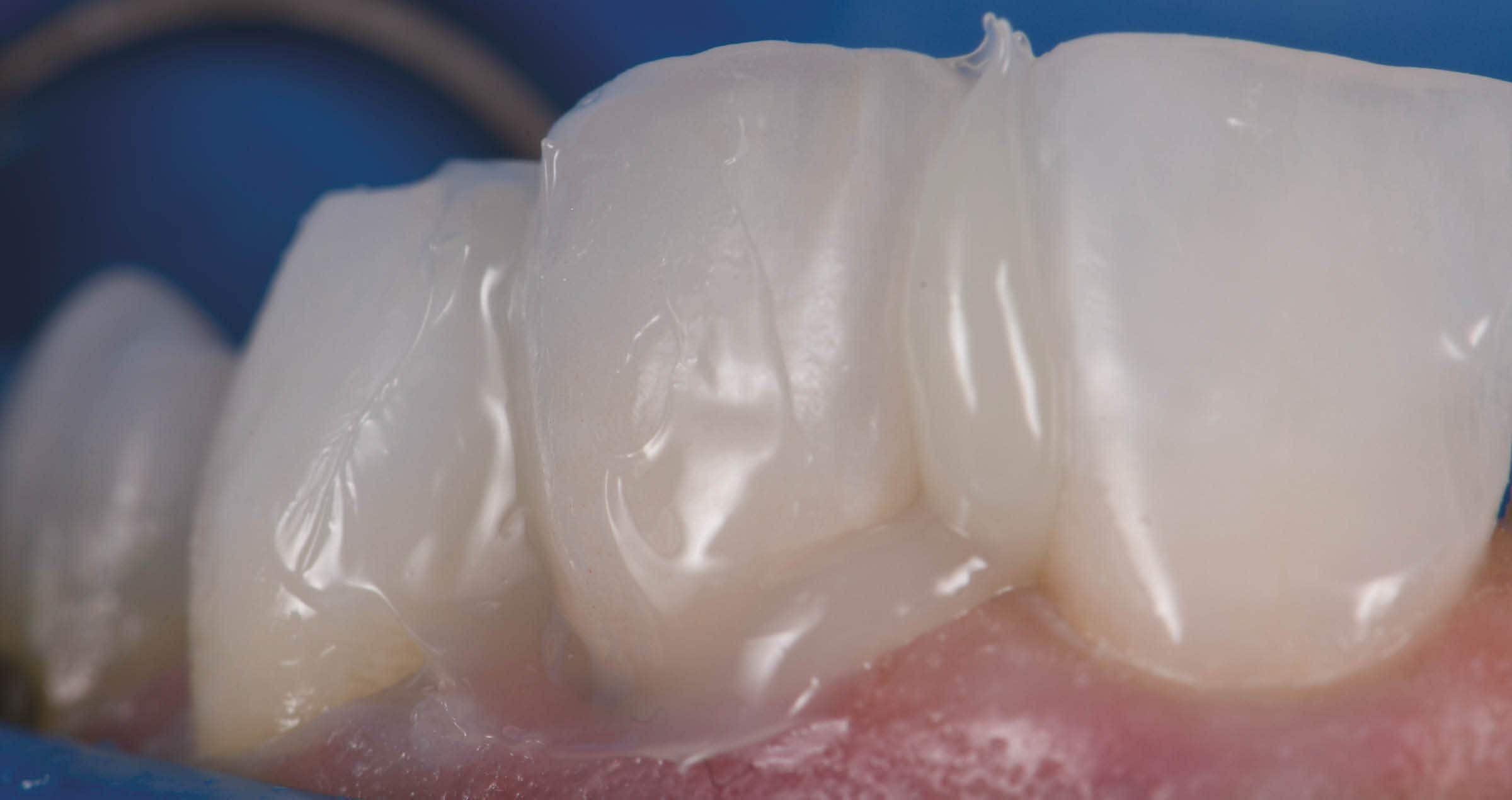

In the present case, the tooth and the fragment now needed to be reconnected. For this purpose, CLEARFIL MAJESTY™ ES-Flow (A2 Low) was applied to the tooth structure. The fragment was then repositioned with a silicone index, held in the right position with a plier and light cured. To obtain a smooth margin and glossy surface, the restoration was merely polished. The patient presented after 1.5 years for a recall and the restoration was still in a perfect condition.

Fig. 15. Reconnecting the fragment with the tooth structure.

Fig. 16. Treatment outcome.

Why is it important to adhere to the product-specific protocols?

Universal adhesives contain lots of different technologies in a single bottle. While this fact indeed allows users to rationalize their clinical procedures, it also requires some special attention. As every highly developed material, universal adhesives need to be used according to the protocols recommended by the manufacturer. In general, materials may only be expected to work well on absolutely clean surfaces, while contamination with blood and saliva is likely to decrease the bond strength significantly. Depending on the type of universal adhesive, active application is similarly important, as is proper air-drying and polymerization of the adhesive layer. In addition, care must be taken to use the material in its original state, which means that it needs to be applied directly from the bottle to avoid premature solvent evaporation or chemical reactions. When adhering to these rules, universal adhesives offer several benefits from streamlined procedures to simplified order management and increased sustainability, as fewer bottles are needed and likely to expire before use.

Dentist:

DR. JOSÉ IGNACIO ZORZIN

Dr. José Ignacio Zorzin graduated as dentist at the Friedrich-Alexander University of Erlangen-Nürnberg, Germany, in 2009. He obtained his Doctorate (Dr. med. dent.) in 2011 and 2019 his Habilitation and venia legendi in conservative dentistry, periodontology and pediatric dentistry (“Materials and Techniques in Modern Restorative Dentistry”). Dr. Zorzin works since 2009 at the Dental Clinic 1 for Operative Dentistry and Periodontology, University Hospital Erlangen. He lectures at the Friedrich-Alexander University of Erlangen-Nürnberg in the field of operative dentistry where he leads clinical and pre-clinical courses. His main fields of research are self-adhesive resin luting composites, dentin adhesives, resin composites and ceramics, publishing in international peer-reviewed journals.

References

1. Van Meerbeek, B.; Yoshihara, K.; Van Landuyt, K.; Yoshida, Y.; Peumans, M. From Buonocore‘s Pioneering Acid-Etch Technique to Self-Adhering Restoratives. A Status Perspective of Rapidly Advancing Dental Adhesive Technology. J Adhes Dent 2020, 22, 7-34.

2. Kuno Y, Hosaka K, Nakajima M, Ikeda M, Klein Junior CA, Foxton RM, Tagami J. Incorporation of a hydrophilic amide monomer into a one-step self-etch adhesive to increase dentin bond strength: Effect of application time. Dent Mater J. 2019 Dec 1;38(6):892-899.

3. Nagura Y, Tsujimoto A, Fischer NG, Baruth AG, Barkmeier WW, Takamizawa T, Latta MA, Miyazaki M. Effect of Reduced Universal Adhesive Application Time on Enamel Bond Fatigue and Surface Morphology. Oper Dent. 2019 Jan/Feb;44(1):42-53.

4. Fehrenbach, J., C.P. Isolan, and E.A. Münchow, Is the presence of 10-MDP associated to higher bonding performance for self-etching adhesive systems? A meta-analysis of in vitro studies. Dental Materials, 2021. 37(10): 1463-1485.

5. Van Meerbeek, B., et al., State of the art of self-etch adhesives. Dental Materials, 2011. 27(1): 17-28.

6. Pashley, D.H., et al., State of the art etchand-rinse adhesives. Dent Mater, 2011. 27(1): 1-16.

7. Vermelho, P.M., et al., Adhesion of multimode adhesives to enamel and dentin after one year of water storage. Clinical Oral Investigations, 21(5): 1707-1715.